A rambling meditation on women and men

Your urge shall be for your husband, and he shall be your master. – Genesis 3:16

In Genesis, Woman exists before Eve. Woman is the partner of man, his complementary help-mate. In the second account of creation she is formed from the side of Adam; who was Adam before? Rashi wrote that Adam was androgynous before the creation of woman - God created Adam in His image, incorporating the masculine and feminine. In the

Bereshit Rabbah commentary, woman is attached to Adam, but in such a way that he cannot see her and be made whole until she is separated from him, and can see his mirror image. Once he sees her, Adam calls her "woman, for she was taken out of man." It is only after the Fall that Adam re-names the woman Eve, "because she would become the mother of all the living." Woman: identified as part of the man who makes him whole, his inspiration and helper; Eve: identified through procreative ability, bound to longing for and submissiveness to her husband. The latter is God's curse for women.

[Note: I much prefer reading midrash for notes on women than that of the Church Fathers. At least when reading writings in the Jewish tradition, I can easily dismiss the misogyny. When misogyny is found in the writings of saints in one's own Church, I want to hurl objects.]

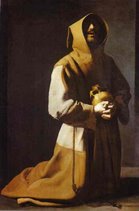

Women have struggled with the tension, as Croce writes of, "sexual complicity in conflict with individual freedom.” Perhaps this is why I have always thought of male and female celibacy so differently. For men, celibacy is discipline, restraint, and bearing the burden of lack of biological progeny. For women, celibacy is freedom, a return to Eden, unburdened of the longing for a man. In the consecrated life, it's also the gift of Christ as spouse, so that the admonishments of Colossians 3:18, Ephesians 5:21-32, and 1 Peter 3:1 no longer seem overwhelmingly cumbersome.

Every man has a Don Quixote in him. Every man wants an inspiration. For the Don it was Dulcinea, a woman he sought in many guises. I myself think that the same is true in life, that everything a man does, he does for his ideal woman. You live only one life and you believe in something and I believe in a little thing like that. It has worked so far. It will last me. - George Balanchine, 1965.

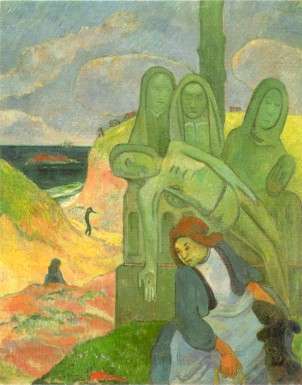

It has always fascinated me that some men long for the original woman, the woman separated from his side. We can enter into the dangerous territory of men who place women on pedestals, and the virgin/whore complex, and yet there is something elemental and primitive about a man's longing for his muse. In the literature of every age, there are mortal men who desire and aspire to conquer women or women-like creatures. While there are several meanings to this including their unattainability (tied to the taming of nature), there is also the longing for the help-mate and inspiration. The desire to proclaim the words of Adam to the chosen woman, "this now is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh." The love for the Blessed Virgin in plastic art and hymns is tied to this - she who is Woman in John's Gospel and Vision.

I want to see the world through you; for then I shall not be seeing the world but only you, you, you! I have never seen you without thinking that I should like to pray to you. I have never heard you without thinking that I should like to believe in you. I have never longed for you without thinking that I should like to suffer for you. I have never desired you without thinking that I should be allowed to kneel before you. - Rainer Maria Rilke to Lou Andreas-Salomé, found in Holthusen’s Portrait of Rilke: An Illustrated Biography (1971). Andreas-Salomé, by the way, was a muse for Nietzsche, Rilke, and Freud.

But how does a woman carry on the life of the muse, without being overcome by the longing 'to be weighed down by the man's body' as Kundera writes? How does she not turn into a Medea? There is the awful example of Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, lovers for ten years. There are also the attenuated careers of women like Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel. However, they were artists in their own right. [See Kavaler-Adler’s

The Creative Mystique: From Red Shoes Frenzy to Love and Creativity (1996) for a full run-down on object relations psychotherapy to understand the sense of self and separation from the male ego that must occur for women artists to gain control of their lives according to this theory.] What is the average woman to do? How is she to be Woman to a man?

[Note: Camille Claudel (1988) directed by Bruno Nuytten, with Isabelle Adjani and Gérard Depardieu is a fine film. However, there are two significant disappointments with this film: the failure to address the influence of Claudel on Rodin’s artwork, which according to some critics, may have been profound., and the psychology behind Claudel’s breakdown – this is beyond a woman who is angered that her lover continues to have other affairs.]

Aimai-je un rêve? - Mallarmé, L'après-midi d'un faune

In Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), James Stewart seeks to re-create a lost-love (played by Kim Novak). In so doing, questions arise as to how much we ever know and love our beloved. Do we subtly train our lovers to be who we want them to be, do we make them into figments of our imagination who we love only as projections of ourselves? Were Adam and woman originally a complete and complementary projection of each other?

Now Jocasta kneels on the floor at the foot of the bed and then she rises with her leg close to her breast and to her head, and her foot way beyond her head, her body in a deep contraction. I call this the vaginal cry; it is the cry from her vagina. It is either the cry for her lover, her husband, or the cry for her children. - Martha Graham on her dance Night Journey, in her autobiography Blood Memory (1991)

The cry for the lover, the need for a man (even if that man happens to be one's believed-to-be-dead son, taken as lover and husband). Can women escape the curse of Genesis, other than through the consecrated life? In the third episode of Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage (1973), after Johan (Erland Josephson) has told his wife Marianne (Liv Ullman) that he is having an affair and is leaving her that very morning to be with his mistress, after the outbursts and crying, she calmly helps him pack his things. She reminds him that he forgets his toothbrush. This is one of the oldest questions of woman to man: how can you live without me? We are symbiotically joined, how can you turn away?

Give me children or I shall die. - Genesis 30:1

Rachel's cry to Jacob earns her a rebuke, for should she not know that woman has a purpose other than procreation and that children are only God's to provide? The meaning of barrenness is only understood through the light of the New Testament's Virgin and Church. And yet women are still confined by the Fall into their role as Eve, with their procreative abilities paramount in importance.

Leila (1996), directed by Dariush Mehruji, is an Iranian film set in modern day Tehran (so husband and wife do not physically touch, and she is dressed in a black chador throughout). Leila (Leila Hatami) and Reza (Ali Mosaffa) are a married couple, happy and in love. But after a year of trying for children, they discover that Leila is infertile. Thus begins the dilemma: should Reza, an only son, take a second wife (this is Iran and Islamic culture, after all) in order to have a son of his own for the family? Reza's mother (Jamileh Sheikhi) batters her daughter-in-law with fears that Reza will come to not love his own wife if he does not have a son of his own. Reza attempts to re-assure Leila, "All I want is your happiness." Nevertheless, Leila decides to encourage Reza to take a second wife. As he interviews women that a matchmaker has set up for him, she takes strolls in a park or along the sidewalk alone, made unimportant by her infertility. After meeting each prospective bride, Reza picks Leila up and they joke about the qualities that the woman had until one day Reza expresses his approval for a woman he has interviewed. They marry, and as Leila listens in the darkened guest bedroom as her husband and his new bride walk up the stairs of their house (the new bride's dress percussively hitting each step, like the pounding of Leila's fearful heart in her own ears), to the room where their marriage will be consummated, she bolts and leaves. She cannot share him afterall, and cannot sit in silence with the person who she has become: a shadow of her husband.

On the face of it, this is a feminist movie about the denigration of women into child-bearing vessels. However, it is also about two people who are totally in love, and yet, as Jane Shapiro names it, practice "intimate terrorism." They are so concerned with the other that they become passive aggressive. They dare not speak completely truthfully. Yes, Leila's mother-in-law is practically a Gorgon Greek chorus standing in for Iranian society, but the heartbreak of Reza and Leila is in how they subtly turn on each other. She fears losing him, she longs for him, and he fears disappointing her. A woman locked in the curse of the Fall.