‘Father, have you never thought of the difference in the soil, the difference in the water?’

‘We have planted the sapling of Christianity in this swamp.’

The fictional missionary, Rodrigues, is told by a fictionalized Ferreira, the Portuguese Provincial who apostatized in 1632, that the Japanese do not actually believe in the Christian God; they would not recognize Him. Rodrigues, who is never tortured in the pit himself but instead is tortured by listening to the moans of people in the pit, hung there until he, a foreign priest, will apostatize, begans to wonder if these Japanese are suffering, dying, for a God he does not believe in. (This part was very controversial among the Japanese Christian community when Silence was published.) The ending of Silence is ambiguous - it seems as if Rodrigues has lost his faith, though perhaps the internal struggle remains.

Is Christianity a 'Western' religion? Do other cultures that encounter it, if they seem to accept it, really only incorporate what is native to their culture with a shallow veneer of the Christian one?

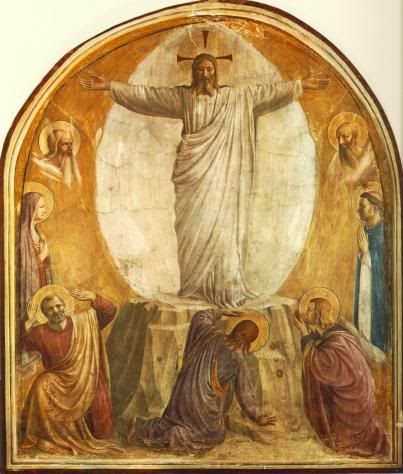

The Christian God, of course, is one Whom everyone has access to simply by their share in humanity. The Almighty is not like the gods or guides in other religions, where specialized knowledge is needed to experience the infinite. No, the Christian God is the Incarnate God, united to humanity. He places Himself on the Cross, spreading His arms horizontally across the earth and vertically uniting heaven and earth. But is the language of the Christian God, God as lover, both father and mother, only understood in Western culture? Can that understanding of God and of human person only be understood by those shaped in Western civilization (and by 'understood,' I mean internal understanding, the kind that seeps into bone, sinews, and blood, not merely intellectual agreement.)

Endo's experience as a Japanese Catholic and his decision to write Silence (from the preface):

I received baptism when I was a child….in other words, my Catholicism was a kind of ready-made suit….I had to decide whether to make this ready-made suit fit my body or get rid of it and find another suit that fit.…There were many times when I felt I wanted to get rid of my Catholicism, but I was finally unable to do so. It is not just that I did not throw it off, but that I was unable to throw it of. The reason for this must be that it had become a part of me after all….Still, there was always that feeling in my heart that it was something borrowed, and I began to wonder what my real self was like. This I think is the ‘mud swamp’ Japanese in me. From the time I first began to write novels even to the present day, this confrontation of my Catholic self with the self that lies underneath has, like an idiot’s constant refrain, echoed and reechoed in my work. I felt that I had to find some way to reconcile the two.Endo's words continue here (bolding is mine, of course):

For a long time I was attracted to a meaningless nihilism and when I finally came to realize the fearfulness of such a void I was struck once again with the grandeur of the Catholic Faith. This problem of the reconciliation of my Catholicism with my Japanese blood…has taught me one thing: that is, that the Japanese must absorb Christianity without the support of a Christian tradition or history or legacy or sensibility. Even this attempt is the occasion of much resistance and anguish and pain, still it is impossible to counter by closing one’s eyes to the difficulties. No doubt this is the peculiar cross that God has given to the Japanese.We could always invoke the superiority of Western civilization here, though I don't think that adequately addresses the issues of belief that Endo raises. On Catholicism (I also note here that Endo's comments are his own, and should not be taken as representative of all Japanese Catholics):

But after all it seems to me that Catholicism is not a solo, but a symphony….If I have trust in Catholicism, it is because I find in it much more possibility than in any other religion for presenting the full symphony of humanity. The other religions have almost no fullness; they have but solo parts. Only Catholicism can present the full symphony. And unless there is in that symphony a part that corresponds to Japan’s mud swamp, it cannot be a true religion. What exactly that part is – that is what I want to find out.This, as Johnston correctly points out, is also the dilemma of modern Catholicism. Western civilization has lost its moorings. It seeks to deny the inheritance of the Western tradition. Does a way exist for Christianity (Catholicism in particular) to be loosed from the Western heritage and survive in the brave new world? Part of what the changes in the liturgy accomplished was a sort of planting of the tree of Catholicism in the swamp of multiculturalism (read my thoughts on that here), among many other 'isms.' But that is not where its roots are. Can it grow there? Is it less 'true' if it cannot grow there? Should it, as Endo would perhaps argue, be able to grow there?