“Love can make man a beast. Love can beautify ugliness.”The genesis of many of our popular Western European fairy tales is in the Middle Ages (the first written versions can usually be found in the Renaissance).

The motifs of a young woman on a journey, step-parents who are neglectful or lustful, in-laws who are spiteful and vengeful, and dreamy Prince Charmings partly developed out of a time when young children often experienced the death of a parent and the guardianship of a step parent or other family members and of arranged marriages, a time when young girls could be sent far away from their homes, placed in the world of their future groom, and could only hope that he would love them enough to walk through fire and fight dragons and be so entranced by his bride’s charms that he would not abandon her (for war or other conquests).

Dreams of true love and partnership in a world of chance and fortune. On another level, fairy tales appeal to our desire for the fantastical and supernatural in our world. If one is not too jaded, if one has the simplicity of a child, "once upon a time" becomes possible in the present.

Folklorists can characterize all fairy tales into several basic types and themes that recur across locations and cultures. I will not get into fairy tales, categories, and archetypes here; all I’ll say is that I once read a book of folk stories from Central European gypsies and it was fascinating how frequently the devil appeared in these stories to steal children and young women. Hmm.

[First rant: A relative did not want his children exposed to fairy tales, because of the ‘absence’ of God in them (and the magic and witches). Of course, almost all the characters in a good fairy tale are forced to make moral choices between good and evil. Passivity, in a fairy tale, will get you stuck in slumber for a hundred years or trapped in a tower. “Proper” moral choices are awarded with supernatural favors (be it through fairies or magical animals). This did not mean that it occurs in a ‘God-less world.’ Now if one wants to argue about tales that take place in a God-less world, one can look at the Harry Potter series.]

Children like real (play) terror; they like to be scared while in safe confines. Give me the old Disney movies, when the Queen of Hearts (Alice in Wonderland, 1950) is so loony that there’s real bite in her “off with their heads!” – the incompetence of her silly card soldiers is the salvation of her prisoners - or the glimmeringly evil and vamping Wicked Queen in Snow White (1939). Maleficent (The Sleeping Beauty, 1959) generated nightmares for years – she just looked like pure evil even before turning into a fire-breathing dragon (insert my sister’s predictable comment: “It’s the ram’s horns! Gosh, you’re SO STUPID!”). She talked about the “powers of hell,” and to this day I can barely listen to Maleficent’s theme music even though in the original ballet it’s the music for the harmless pas de deux of Puss N’Boots and the White Cat and has no malevolent overtones.

Disney fairy tale films really lost their energy, however. In The Little Mermaid (1989), the story is re-imagined for our mermaid, Ariel, to survive and be reunited with the prince. Like Hans Christian Andersen, I much prefer – and did even then – our scantily clad swimmer with dreams of human love committing suicide in the end. A bit morbid perhaps, but it taught a vital 19th century social lesson about the importance of class distinction. Besides, I’m unsure what kind of positive message can be gleaned from the story of a creature who sells her soul (oops, her voice) to an enemy who wants to enslave her people in exchange for physical transformation, and ends up getting both her voice back and the cute boy in the end. Girls should do ABSOLUTELY ANYTHING for love: don’t stop at physical mutilation and cooperation in the subjugation of others when a dreamy prince is the end goal. There’s a reason why the original fairy tale ends the way it did.

[Second rant: Even as a 10-year-old, I recognized that The Little Mermaid and other Disney fairy tale fare were overt attempts of indoctrination into white patriarchy and the notion of ‘love’ as female submission, and I wasn’t buying it. In the Hughes Brothers’ American Pimp (1999), while the pimps are talking about physically and emotionally abusing their prostitutes, the women are expressing hopes that the pimp will fall in love with them and be with them forever. This notion of female romantic love, torn asunder from the social constructs that once necessitated it, now work their seductive and oppressive powers on women in a society divorced from a male obligation to women that used to be compulsory. Men always want it both ways. Down with matrimony!]

In Peau d’Ane (Donkey Skin, 1970) directed by Jacques Demy, a king (Jean Marais) decides he must marry his own daughter (Catherine Deneuve), for he has promised his now-deceased wife (and mother of that daughter) that he will marry the most beautiful woman in the kingdom (shades of St. Dymphna). The Princess is quite willing to go along with this: “All little girls, asked who they want to marry when they grow up, say 'I want to marry daddy.' “ The Princess is put on the correct moral path by her fairy godmother, who tells her to delay this fate by requesting dresses the color of the weather. And the dresses that the costume designer creates are really the only magical part of this fairy tale adaptation. The music by Michel Legrand is horrible, the supposedly surrealist artistic schemes are awful. But I may be allergic to Demy’s films, as I nearly prayed for deafness when watching The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). And BTW, Donkey Skin is a real fairy tale collected in Charles Perrault’s volume of fairy tales (1697). The donkey excretes gold and jewels for the kingdom before the Princess takes his hide (having requested it from her father) and then hides under it and flees the country, only to be found by a prince, and so on. I eagerly await Disney’s sanitized version of this one.

In Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991), the beast is as cuddly as a teddy bear, the kind of sentient animal you can take to bed without fear of ravishment, and little girls I babysat for did. Unfortunately, the drama of the fairy tale is thrown off by both the Beast’s cuddliness (see below) and the sub-story of Belle’s desire for female empowerment (grrrl power), when all she can possibly become is lady of the manor. She is supposed to civilize the beast within a man so she can then be a loving wife to him, not conquer the world by being literate and well-read. But she’s reading nothing but stories about sword fights and princes, so she’s not even the latter.

Beauty and the Beast (first written down in the 18th century) is about woman’s attraction to male virility, Samson and Delilah redefined, from sexualized woman to male redemption through female beauty. The beast represents both what is untamed and what is highly potent. The story is the conquering of the adolescent girl’s fear of the wedding chamber – doing it at her father’s request and for the survival of the family - and her hopes to transform a prospective groom into faithful and loving partner. As with so many other fairy tales, it’s partly about sex. [Another example of the beauty and the beast tale on film is King Kong (1933); a work as different as Raging Bull (1980) also utilizes it.]

"There is no master here but you."

Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (1946) is the best fairy tale on film I have seen. With Henri Alekan as cinematographer, Christian Bérard as production “illustrator,” and Georges Auric as composer, not including the luminaries hanging around the set, it’s a major collaboration among prominent French artists of the first half of the 20th century. (There’s also an entire side-story of how difficult it was to make this film in post-War France.) Depending on one’s mood and experience, it’s a tale about personal transformation through beauty, the power of love and mercy, the thrall of sexual potency, the acceptance of death, or an S&M flick heavy on the subtlety. Is it Symbolist? Is it Freudian?

Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête is filled with double meanings. Beauty (Josette Day) lives with her sisters (two harpies who make her do all the housework), a ne’er do well brother, and an aging father. Her brother’s friend, Avenant (Jean Marais, who also plays the Beast and Prince Ardent), is in love with her but she rejects him because she must care for her family. Her father gets lost in the forest and finds himself at the Beast’s castle. His fatal error is to pick one of the roses in the beast’s garden, and so the story continues….

The first half-hour of the film comes straight out of a Vermeer exhibition. It is only once Beauty decides to spare her father’s life by mounting Magnificent, a huge white horse, and saying the magic words, “Go where I want to go. Go, go, go!” that the magic takes over. The scenes of her arrival in the castle, her movement in her slow motion and her steady glide through a corridor, are pure fantasy. Her door, her mirror, and other inanimate objects talk to her, and her bed cover invites her to enter – every little girl’s dream room, and every adult’s nightmare of being constantly watched. Real arms hold the candelabra, real faces are along the mantel, watching. The forest outside encroaches into her room, untamed nature waiting for both her dominance and her surrender. When she must leave him to see her dying father, she cries tears that turn into diamonds on her cheek, and her grand jewels turn to rope in the hands of her greedy sisters. She has become part of a different world, one of transformation.

The Beast (Jean Marais) is a predecessor of the Wolfman and Chewbacca, awkwardly wearing clothes meant for an 18th century lord. With fur smoking from the conquest of a kill, he asks Beauty not to look at him. She does so anyway, and her eyes have the same gleam as Deneuve’s housewife by night/masochistic prostitute by day character does in Buñuel’s Belle du Jour (1967) when looking into a keyhole, watching a fellow prostitute with her client, turning towards the camera to say “that’s disgusting!” and then going right back to voyeur behavior. She is attracted to that which repulses her. (It’s probably no coincidence that the room that holds the Beast’s earthly treasures is called “Diana’s Pavilion,” and anyone who enters without the golden key is killed.) Beauty redeems him through mercy and love and his own longing to be civilized through nothing more than the presence of her beauty. (There is an apocryphal story that Marlene Dietrich, when first watching the film, screamed “Give me back my Beast!” during the scene following transformation.)

And yet even the ending is open to several interpretations: Beauty admits to having loved her suitor Avenant, and the two lovers fly through the air and seem to ascentdto the kingdom of Prince Ardent. There are moments that look like Rubens’ Assumption of the Virgin (1626). Has this really been about Beauty’s acceptance of death, her conquering the fears of going into the unknown that exists beyond the grave? Is the rejected and suffering Beast a Christ figure? Cocteau’s film successfully operates on all these levels, with so much imagination and belief in magic added.

[Final note: Philip Glass wrote an opera to this film that is synched to the film track on the most recent DVD release of this film.]

.jpg)

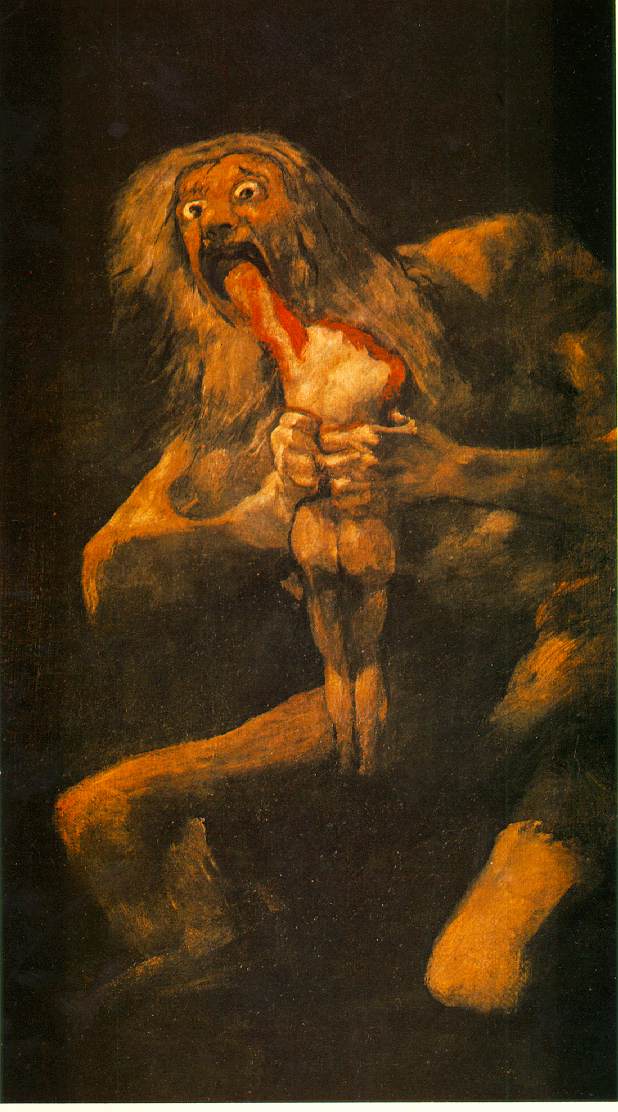

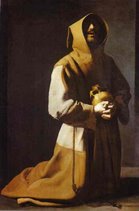

Paintings are Edward Burne-Jones Sleeping Princess (1880) from Briar Rose, Gustave Moreau Orpheus (1865) and Odilon Redon Orpheus (1903); I don't like much of the artwork from fairy tales, so I've included Symbolist works instead. Some days the art I choose is directly related to the subject, sometimes not.

.jpg)